In 1917, in response to the publication of Einstein’s theory, Frank Dyson, the Astronomer Royal and director of the Royal Observatory Greenwich, published a paper reporting his failure to measure a significant displacement for the few stars visible on eclipse plates taken in 1905. He predicted that the total eclipse in 1919 would provide a much better chance of success, as the Sun would be situated in the richer star field of the Hyades.

Einstein’s theory had successfully explained a small discrepancy in Mercury’s orbit around the Sun, but his prediction of the gravitational redshift of absorption lines in the Sun had not been confirmed.

Kennefick (2012) suggests that the few physicists and theoreticians, such as Eddington who understood Einstein’s theory, needed no observational proof, but many astronomers, including Dyson and the wider world were highly sceptical of the theory, so the results of the 1919 eclipse would be crucial to its acceptance. Kennefick also puts to rest any suggestion that Eddington selected his results to support Einstein’s prediction.

An unsuccessful attempt was made to measure the deflection, by a group from the Lick Observatory at the total eclipse of 8 June 1918.

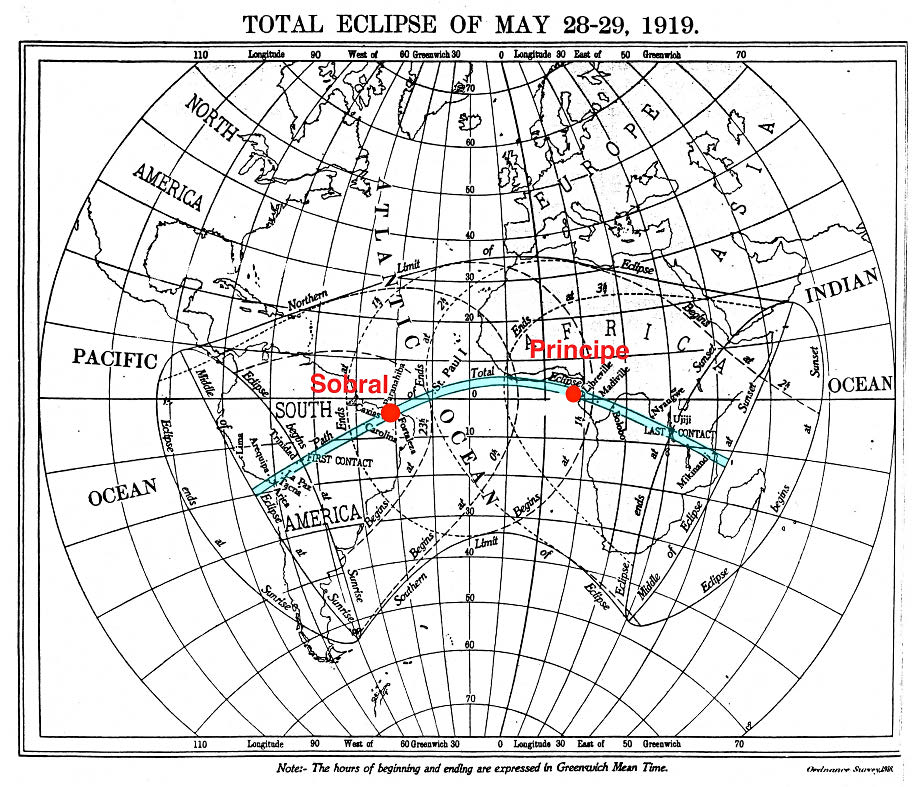

The line of the 1919 total eclipse crossed the equator, stretching from South America to Uganda, giving almost 6 minutes of darkness, during which the Sun and surrounding stars could be photographed.

A British expedition was organised under the direction of Dyson. It was decided that two groups of two observers would be sent. One group, consisting of staff from the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, went to Sobral in Brazil. The second group, from the Cambridge Observatory, went to the Island of Principe, a small volcanic island 220 km off the West African coast. The Greenwich group consisted of Andrew Crommelin and his more junior colleague Charles Davidson. The Cambridge group consisted of the Observatory’s Director, Arthur Eddington, and Edwin Cottingham who looked after the Observatory’s clocks. The expeditions were supported and partially funded by the joint standing eclipse committee of the Royal Society and Royal Astronomical Society.